Breadcrumb

Malaria: Drug resistance and underfunding threaten progress towards eliminating killer disease

The parasitic mosquito-borne disease is both preventable and curable but it remains a serious and deadly global health threat – claiming hundreds of thousands of lives – mostly among young children and pregnant women, predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa.

The WHO’s latest annual update shows impressive progress since 2000: intervention has saved an estimated 14 million lives worldwide over the last quarter of a century, and 47 countries are certified malaria-free.

Nevertheless, malaria remains a deadly concern. There were more than 280 million malaria cases and over 600,000 malaria deaths in 2024, with 95 per cent of cases concentrated in the Africa region – most in just 11 countries.

Resistance ramps up

A major stumbling block to the elimination of malaria is the issue of drug resistance, which warrants a separate chapter in this year’s study: eight countries reported confirmed or suspected antimalarial drug resistance, including to artemisinin, a WHO recommended treatment.

To combat this, the report recommends that countries avoid over-reliance on a single drug, while opting for better surveillance and regulatory health systems.

Underfunding – in a region rife with conflict, climate inequity and fragile health systems – is another major cause.

Some $3.9 billion was invested in the response in 2024, less than half the target set by WHO.

The report highlights that Overseas Development Aid (ODA) from wealthy countries has fallen by around 21 per cent. Without more investment, say the authors, there is a risk of a massive, uncontrolled resurgence of the disease.

‘The red lights are flashing’

“Malaria is still a preventable and treatable disease, but that may not last forever,” warned Dr. Martin Fitchet, the CEO of Medicines for Malaria Venture, a not-for-profit organisation that focuses on delivering new antimalarial drugs, at a WHO press briefing to preview the report.

“We have to act now to increase the scope and coordination of surveillance, so we're not flying blind, and boldly invest in the innovation of the next generation of medicines, so the parasite doesn't get ahead of us.”

Dr. Fitchet raised the spectre of the crisis which resulted from resistance to the anti-malarial drug chloroquine in the 1980s and 1990s.

This led to a humanitarian disaster, with the loss of millions of lives, mainly children.

“Today we can see from this report that the red lights are flashing again with an increasing number of resistant mutations emerging in the African continent. We need to ensure that we prolong the resilience and the effectiveness of the medicines we have now.

“But our long term resilience and eventual victory in the fight against malaria depends on developing the next generation of anti-malarial medicines.”

He said the “complexity and scale of the challenge we face means that no single tool or actor can succeed alone,” he concluded, calling for partnerships that span the whole human health sector including “industry, global health agencies, academia, physicians, investigators, civil society, communities, and funders.”

Key facts from World Malaria Report 2025

- Global burden: In 2024, there were 282 million malaria cases and 610,000 deaths, a slight increase from 2023.

- African Region impact: Africa accounts for 94 per cent of cases and 95 per cent of deaths, with 75 per cent of deaths among children under five.

- Progress since 2000: Malaria control efforts have averted 2.3 billion cases and 14 million deaths globally.

- Countries certified malaria-free: 47 countries and one territory have achieved malaria-free status, including Egypt and Timor-Leste in 2025.

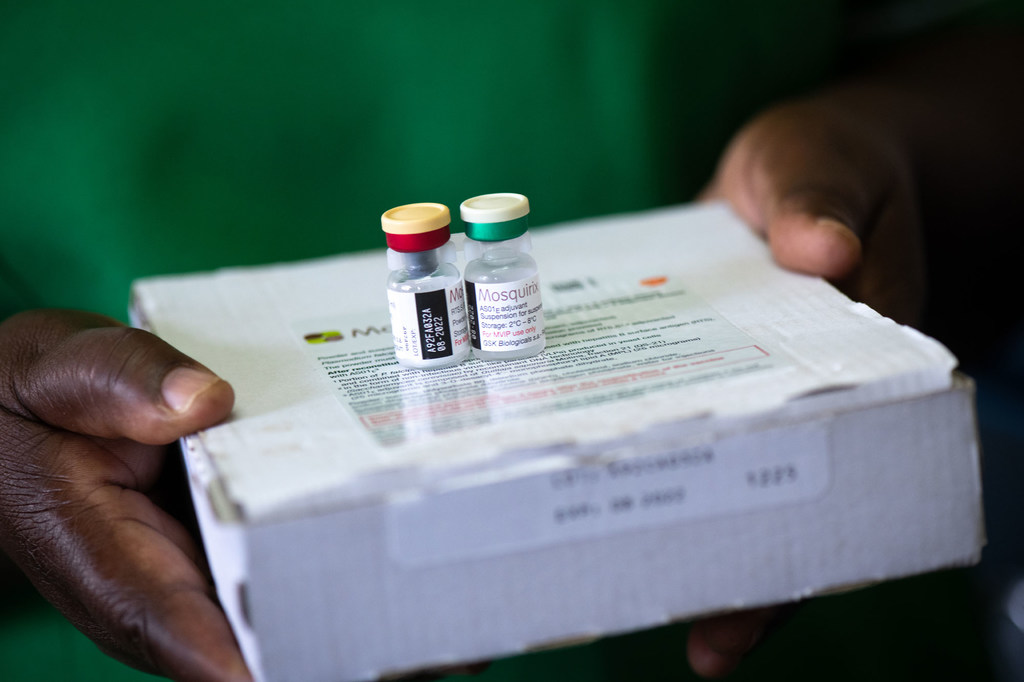

- New tools expanded: Wider use of next-generation insecticide-treated nets, rapid diagnostic tests, chemoprevention, and malaria vaccines.

- Funding gap: Global malaria funding in 2024 was $3.9 billion, only 42 per cent of the $9.3 billion target for 2025.

- Resistance threats: Some malaria parasites have lost the pfhrp2 gene, which means they don’t produce the HRP2 protein that many rapid tests detect. This makes those tests fail even when the person is infected

- Urban malaria risk: Spread of Anopheles stephensi mosquito to nine African countries, increasing urban transmission.