Breadcrumb

SPOTLIGHT - Right to housing highlighted as "staying home" has become watchword for staving off COVID

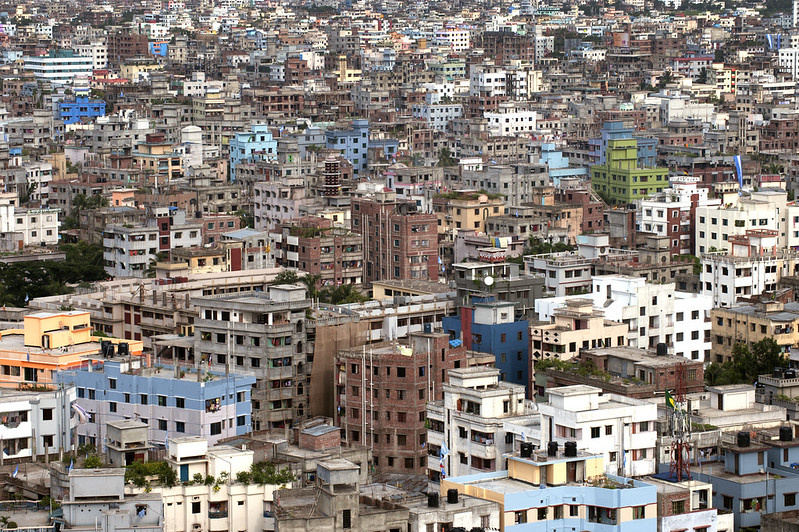

Dhaka, Bangladesh. UN Photo/Kibae Park.

At a time when real estate prices and homelessness are on the rise in major cities, and when households, especially low-income households, are spending an increasing share of their income on housing - the impact of any decision in an area such as housing can have a significant impact on people’s daily lives. Even more so, as Leilani Farha, former Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing, points out in this interview with UNIS Geneva, now that "stay at home" has become the watchword used by governments to ward off the global Covid-19 pandemic.

For six years you were Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing. What was your mandate exactly and what main orientations did you give it?

I was tasked with monitoring the enjoyment of all aspects of the right to housing, in all countries, for all people. It’s a huge and daunting mandate!

I spent a great deal of time analyzing the ways in which the financialization of housing - the process of turning homes into financial assets and investments, usually through hedge funds and private equity firms – was undermining the right to housing in different contexts, in both the Global North and South.

I learned that it has devastating impacts on the people who live in those homes, who are typically subjected to increased rents, decreased habitability and service provision, and increased threats of eviction.

But it also impacts cities more generally – financialization increases local rents and housing prices, making cities unliveable for all but the wealthiest. Financializers will put profit before everything. Recently, one major financialized landlord in the US sent a tenant who was struggling to pay their rent information on how to make money by selling their plasma and their hair! They’re literally suggesting people sell parts of their body to pay the rent!

I also tried to bring the right to housing to a bigger audience. During my tenure I liked to supplement my official UN reports with other forms of media. For example, I showed photos while presenting my thematic report on homelessness at the UN Human Rights Council – a first. And alongside documentary filmmaker and director Fredrik Gertten, I made a feature length movie called PUSH, about financialization around the world.

Could you tell us about your day-to-day work? What are the most important aspects of the job of a mandate holder?

Rapporteurs are uniquely situated to carry messages from the ground to the highest offices. I always felt the role of Rapporteur is akin to being a public servant albeit on the global stage. I felt a duty to say what needed to be said to protect and realize the rights of marginalized and disenfranchised groups. As the first lawyer to occupy the Rapporteur position on adequate housing, I wanted to show governments and NGOs that it actually means something to “do” the right to housing, that it is concrete and can be implemented once understood.

As Special Rapporteur you also must present two reports per year – one to the Human Rights Council and one to the General Assembly. These reports are on topics of your choice – things you recognise as being pressing issues for the right to housing – and they require a lot of work. You have to do detailed consultations, lots of research and weeks of drafting.

I spent a lot of time away from my desk, my home, and my own family. I spent a great deal of time on-the-ground in other cities and countries, either on an official visit (of which Rapporteurs do at least two per year) or on an unofficial visit – presenting at conferences. A typical day would be about 14 hours long in back-to-back meetings and site visits. This would include speaking with local or national governments and decision makers to build awareness about the right to housing and guide them towards compliance.

It also involved going to the homes of rights holders, and as experts in their own lives, learning from them about their housing realities. Meeting with people in their homes is probably the most important part of the role, learning how to be an active, respectful listener.

At the end of 2019, you expressed your satisfaction that Portugal had adopted a comprehensive housing law in accordance with one of your recommendations. What was the basis of this success and how would you describe its importance for the Portuguese?

Portugal was one of the countries that suffered most because of the global financial crisis, which had an enormous impact on the enjoyment of the right to housing in the country. Portugal saw increasing housing insecurity and rising unaffordability, and many people were forced into homelessness.

When I visited in 2019, the desperation of people was plain to see – quite simply, the government was not doing enough to respect, protect and fulfil their right to housing. So, the passage of the housing law, in line with the recommendation I made to the government, marked a pivotal moment for the right to adequate housing. The law recognizes that housing is a human right and centralizes vital human rights principles such as participation, non-discrimination, and universality.

The law’s success, and its importance to people in Portugal, rests on the power of its provisions to bring about human rights compliant housing. For instance, the law prohibits people from being evicted unless the government provides them with suitable alternative housing. It also ensures that people experiencing homelessness are not denied the ability to obtain services because they don’t have an address – something that is very common in other countries and leads to a whole host of negative outcomes, including the entrenchment of poverty and homelessness.

Laws such as these are vital as they give real, justiciable in a court of law, substance to international human rights law. By passing this law, Portugal is leading by example and has helped set an important precedent for other States that these laws are possible, effective, and necessary.

Do you have any other examples of actions you took that ultimately had a real impact and made a difference in people's lives? What accomplishment are you most proud of?

The Rapporteurship provides you with an international platform where you have such a chance to make real change. It’s a huge responsibility. Alongside my team, we had many victories I am proud of.

At the end of my tenure, I published the Guidelines on the Implementation of the Right to Housing where I provided a framework for governments and other actors to progressively realize the right in line with their obligations. I know that report is being used in many countries around the world to generate a shift in how housing is seen and how housing policy is drafted and implemented. Just the other day, we learned that the Guidelines were being used to address homelessness in Los Angeles. Before that, we had heard they were being used to inform discussions in Ireland regarding a Constitutional amendment.

Of course, the Covid-19 pandemic also struck the world during my mandate and I very quickly came to realize what a massive impact it would have on housing, and just how important adequate housing was to protect people from the virus. So I quickly set to work drafting a set of Guidance Notes on various aspects of housing, including evictions, financialization, and encampments, to show governments around the world how they should fulfil their human rights obligations during the pandemic. These Guidance Notes are widely referred to and have been used to direct efforts to progressively realize the right to housing during the Covid-19 crisis.

Today you are the director of The Shift, an initiative you launched in partnership with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Tell us more about this initiative.

Whilst Special Rapporteur, I came to realize there was a real need for an organization working globally to secure the human right to housing in line with the international human rights framework. There are so many great housing organisations at the domestic level, but few international voices connecting the dots.

The Shift was originally conceived as a partnership between me as UN Rapporteur, with the OHCHR and United Cities Local Governments (UCLG) in 2017. It was a very purposeful partnership. The OHCHR is the highest human rights body within the UN system and as such commands significant respect. UCLG represents more than 250,000 local governments worldwide, and we all know that cities are on the frontlines of the housing crisis. This three-way partnership seemed strong and relevant.

The Shift launched as an organization in 2020 after I completed my post as UN Rapporteur. Obviously, 2020 was the year the world became almost unrecognizable. It was clear that housing and the global pandemic were inextricably linked. A global movement to secure the right to housing became of even greater importance as “home” became the common prescription used by governments to stave off the pandemic. With more than 1.8 billion people living in grossly inadequate housing and homelessness, ensuring better and more adequate housing in keeping with human rights obligations became ever more urgent. Since the pandemic struck, we’ve been working directly with governments – particularly city governments – to implement rights-based housing strategies. We have also devised model legislation, holding governments to account for specific breaches by issuing Letters of Concern.

People often say to me that The Shift is a good news story – which is exactly what we want it to be!

*From civil and political rights to economic, social and cultural rights, the special procedures mandate holders of the UN Human Rights Council work hard to ensure that human rights are respected and to make a difference in many areas of people’s lives. These human rights watchdogs, appointed for three-year renewable terms, dedicate themselves voluntarily to the protection of human rights.